Freelance Copywriter currently based in

Los Angeles.

A bit about me

I love using writing to tell your story and, admittedly, mine too. I am a movie obsessive that harnesses the power of all that storytelling has to offer to make people pay attention to your brand. If you need some help getting things started or adding in those final touches, keep scrolling for an idea of what I can do for you.

Work

For over a decade I worked as a chef, but I’ve been writing for my whole life. I know how to deliver what people want quickly and efficiently. I’m ready to solve your problems, make you money and answer any questions you might have about deboning a salmon (you never know).

Spec Ad Work

Smart Chef

In response to a workforce too tired to cook, Smart Chef hopes to give your weeknight dinner at home a boost. This spec landing page offers a comfortable welcome to a tired consumer.

Highland Park Farmers Market

The demand for quality, locally sourced food is growing and now more than ever consumers are buying local. This spec flyer for a local farmers market offers simple and cause oriented messaging, letting the market demand do the work.

Smith & Franklin

With over 2 million work place injuries last year alone, workers compensation firms help American families rebuild. This spec landing page lets potential clients know that you are professional without being intimidating,

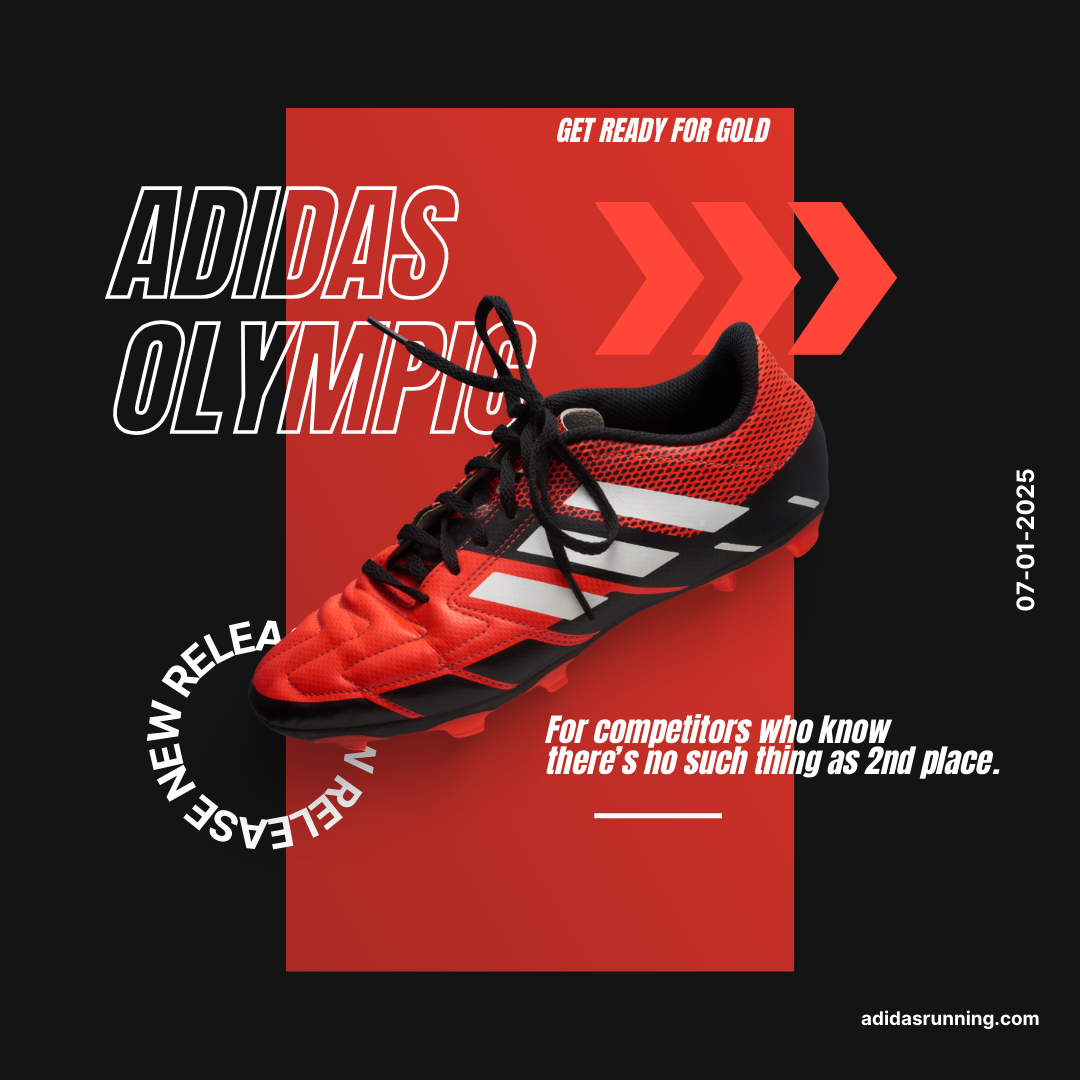

Adidas Olympic

Run faster. Jump higher. Out pace the competition. This spec ad offers a new option for athletes looking to get a head start well before race day.

Bettor’s League

Peanut Butter and Jelly. Milk and Cookies. Football and Parlays. In the ever expanding market of sports gambling, this spec ad gets straight to the point and incentivizes eager bettor’s by simply laying out the possibilities.

Long Format Writing Samples

Whether you need help developing an idea into something more concrete or need fresh insight into the media around us, I can help.

Media Analysis

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, 1962

John Ford’s late period masterpiece is a meditation (at least as meditative as his tendencies would allow) on the twilight years of the American West as it disappears under the blanket of progress.

The film opens with Jimmy Stewart traveling back to Shinbone, a stand-in for any frontier town, for the first time since ascending the ranks in Washington. At this point, Shinbone is basically a novelty, not nearly the cutthroat locale it was decades prior, and Stewart saunters around the city that platformed his successes like a college graduate returning to their hometown. While he is clearly on a mission, he takes note of the progress as he passes through town, shooing away eager journalists in his path. He ultimately reaches his destination, a dusty, disheveled funeral parlor to pay his respects to a man that Shinbone has long since forgotten. Curiosities peaked, the local newsmen swarm, desperate to understand the importance of the man in the coffin, to which Stewart begins to unfurl the truth of the beginning of his own myth.

What takes place next is a tight parable about 3 stages of The Old West intersecting. The lawless, the stabilized and the modern, the former two yielding in time to the latter. Lee Marvin represents the savage, untamed west as the trigger happy, moral-less Liberty Valance, John Wayne plays the righteous, unshakeable Tom Doniphon, an archetypical mid-era cowboy, and Stewart, playing the educated, dutiful Ransom Stoddard, represents the inevitable, civilized progress drifting in from the East.

Stewart at first has a hard time grappling with the rules of his new home, butting heads with Wayne as he firmly, but honestly lays out the facts of the land. Stewart, a lawyer, refuses to stoop to what he sees as the vigilante justice of the territory, despite the looming threat of Lee Marvin’s whip and revolver. Overtime, as Stewart begins to educate and organize Shinbone, Wayne begins to recognize the end of his era. He sees the woman he longs for latch on to a future that will surely leave him behind, he sees the town around him begin to modernize and the people in it becoming self reliant, no longer needing his brand of swift justice.

The only threat to that creeping progress is Marvin’s Valance who gnashes like a rabid dog at the signs of change, vowing to deter, by violent means, the oncoming law and order. Wayne recognizes this affront to the advancement set into motion by Stewart and begrudgingly helps by beginning to relinquish his watchful grip on the town to Stewart.

This all comes to a head in an iconically framed, expertly staged shootout between Marvin and Stewart, with Wayne lurking off camera in the shadows. After a bit of back and forth, and a few cheap early shots from Valance, it appears as though Stoddard bests Valance just after the scoundrel vows to “place one between his eyes”. Ultimately, it is Wayne who secretly guns down Liberty Valance from the shadows, knowing that change will only come if he sacrifices his own legend for the sake of modernization, dooming his way of life in the process. Further still, in an act of pure selflessness, he reveals the truth only to Stewart, clearing his conscious, allowing him to rise unburdened.

The glory of Ford’s final opus is just as much in the text of the film as it is in the subtext. Ford is a filmmaker who revolutionized the Western, a genre that Hollywood and moviegoers couldn’t get enough of for the majority of his career, and he was deemed a master of the form nearly two decades before this movie even came out. He lifted the genre into a higher filmic language, codifying it’s sweeping zooms, it’s selfless heroes, and it’s wind whipped tension. Still, with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance he knows his time is up. He returns to black and white, suggesting a nod to the past, and tells a story through the lens of his greatest muse about the end of an era. Few filmmakers have the awareness in the wake of their own reputations to know their time is soon over, but that’s what makes a legend a legend.

The Taste of Things, 2023

I spent a little over a decade falling in and out of love with cooking professionally. It’s what I decided I wanted to do from a very young age, something I went to school for, and something I pursued to the point of physical and emotional deterioration, until eventually, I couldn’t continue. Now it’s been hard to say in the past whether or not I’ve lost the spark for cooking or just lost the blind ambition it takes to push yourself to a high degree in a restaurant setting, but I think I’m starting to unpack it all.

Since leaving Chef-dom behind to dive into some other interests, albeit with a bit less reckless abandon, I’ve had a hard time sorting my feelings about the last 10 or so years of my professional life. The Taste of Things, however, did offer quite a bit of clarity. Cooking is hard, unforgiving work. It’s temporary in it’s output but eternal in the toll it can take on your body and your spirit. Cooking is something that you can love so deeply, but when it’s your job, that love can be stretched so thin under the weight of all the stress and pressure it begins to crack. I’ve known more talented cooks who have been broken down under the weight of their own goals than I’d like to count, but if you have ever had any pure, intrinsic love for food at all, Tran Anh Hung’s culinary masterpiece will reach that love and pull it to the surface, no matter how dormant, tattered or forgotten it may be.

It was clear to me in the first 5 minutes that I was going to have a passionate reaction to this movie. The culinary school I attended as a teen was predominantly French Classical and the opening set piece is as honest and true a representation of what makes that style of cooking so significant as you can achieve. Layers, upon layers, upon layers of flavors are being thoughtfully composed, stocks are being simmered to be strained and then clarified in order to be turned into consommés, to then be infused into sauces, to reinforce dishes composed of the same ingredients. Seasonal, garden-fresh vegetables are served in large identifiable chunks, confidently plated as little individual seals of quality. Specialty copper-clad pans line an incredible French top in a way that act as a preview of what’s to come if you’ve really studied the craft (when the Turbot Poissonnière came out I think I may have audibly gasped). I have such a nostalgic and un-jaded warmth towards this style of French countryside home cooking that long predates the hyper managed fine dining that would plague kitchens across the world when I was getting my own start. This was such an educated and accurate glimpse into the era of cooking that I studied that made me fall most deeply in love with food, cooking and the lore of the industry. (Not surprisingly, the culinary advisor on the film has had 3 Michelin stars for as long as I can remember.)

Even more precious than the way the food is prepared is how our two central chefs talk about what it is they are preparing. When we meet them they are collaborating on a dinner for close friends, all the while offering little tips and morsels for a young girl who eagerly peels vegetables and shells crawfish. Though Pauline’s doe-eyed, yet ambitious persona may seem a bit convenient for the movie, she’s the character that I most related to. I remember a handful of experiences very early in my own apprenticeships where I stood next to celebrated Chefs, who after hours of watching me shuck peas or clean sunchokes would reward me with little spoons of whatever was simmering away on the stovetop, and even better yet, they’d ask me what I thought about it. Binoche’s Eugénie and Magimel’s Dodin are both eager teachers with an honest and spiritual relationship to the food they are cooking. By setting this movie in their home, and not in some brigadier kitchen, you remove the business side of things that tends to poison most chefs love for cooking, and instead you are able to show why they cook. And the movie is very clear about them loving to cook for their friends and for the refinement of their craft, but it is even clearer on their need to cook for each other.

What elevates The Taste of Things even further past the food movies that came before, is it’s central romance and how Dodin and Eugénie express their love for one and other. Any two people can kiss, or fuck or say I love you. But as someone who loves to be fed, there is no more intimate, or true way to truly show that you care then cooking for someone else. Dodin’s plea for marriage, as expressed through what are the most beautiful cooking sequences ever put to film, is a larger display of love in my opinion than anything else someone with his talents can offer.

You can never really, truly cook for yourself. You always have to be cooking for someone else if you really want to reach that sort of mythic greatness this movie alluded to. When he sets off to make his final proposal, the Sun is just peeking into the walls of his kitchen through the blinds and as he sends the ring out to Eugénie with dessert, the whole room is lit with pale, gray moonlight, his breathing heavy from a day of mentally and physically taxing work. That’s love, of the highest, most unrelenting order.

Script Treatment

Here is an example of a script treatment I wrote for someone who needed a little help turning their big idea into a more tangible one.

A little bit more about me

I’ve been writing for as long as I could hold a pencil. I’m a constant victim to good advertising and I’m hoping to start balancing those scales. My goals are to help clients get their ideas across in a way that not only drives consumers to their business, but makes their brand feel human.

In addition, I write long-form and short-form movie reviews & analyses, along with working on various small projects ranging from editorial work to social media management.

I currently live in Los Angeles with my very talented girlfriend and much less talented dog.

In addition to writing and watching movies, I enjoy watching the great athletes of my youth slowly retire one by one, making me feel more and more mortal, one jumbotron tribute at a time.